|

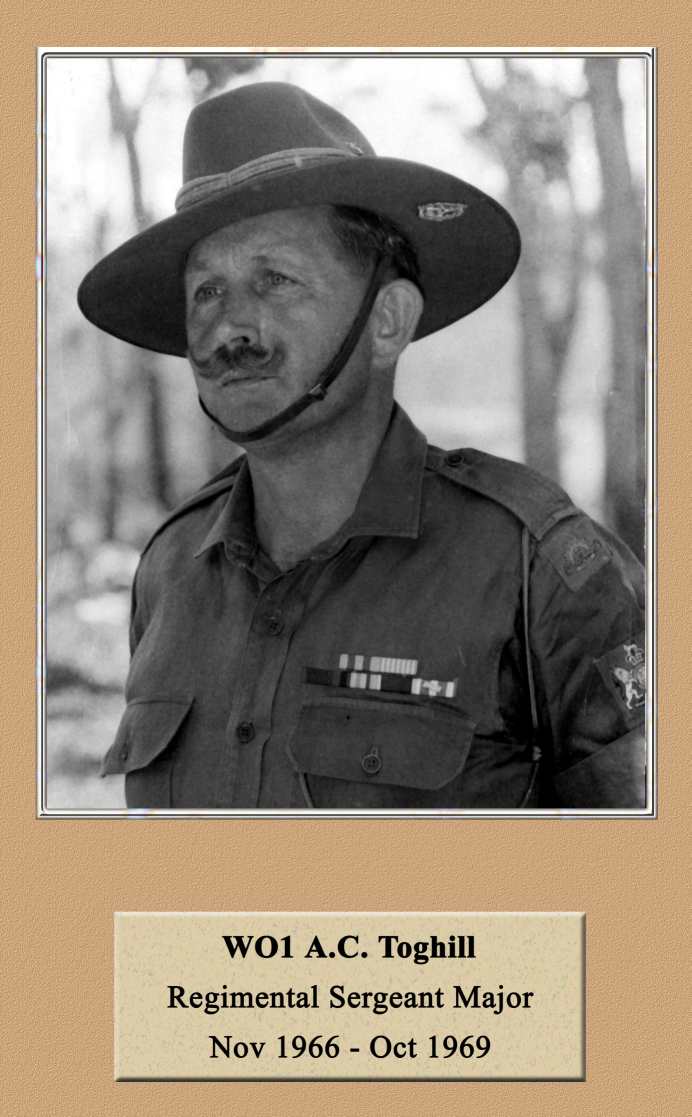

VALE 3rd RSM 4RAR 21-MAY-1929 to 7 SEPTEMBER-2007 RIP |

|

From:

GARRYHESKETT@aol.com

Sent: Thursday, September 06, 2007 11:04 AM

Subject: Mick Kennedy-in Hospital

To: 'Garry Sloane' Sent: Monday, September 03, 2007 9:18 AM Subject: Mick Kennedy-in Hospital Garry, I thought you might want to know that Mick Kennedy (Cpl 4 Section 11 Platoon last tour SVN) is in the High Dependency ward of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital (QEH) Adelaide. He had his right leg amputated below the Knee yesterday. Complications set in after previous surgery to fix foot circulation problem. Mick is in fine spirits as I spoke to him this morning. I also spoke to Faith (Mick’s Wife) and she is ok and relieved it is over as far as the operation went. Mick is on a dialysis program and is currently waiting for a Kidney transplant after he is mobile again. Tel for QEH is 82226000. It is ok to let the troops know. Thanks Garry and take care.-Regards Mick (Stretch). SUBMISSION ON BEHALF OF WALTER HEAGNEY B COMPANY 4RAR Malaysia 1966 1. My name is Roger John Wickham. I was posted as a 2LT to 4RAR from 2 RAR, as a foundation member when the battalion was raised in 1964 and was the original commander of 11 Platoon D Company. I arrived in Terendak Garrison in Malacca with D Company in early September 1965 and deployed to Sarawak with D Company in early April 1966. I was injured in Borneo in June 1966 and was reassigned as the Assistant Adjutant until June 1967. I was then appointed as the Return to Australia Officer to arrange the return by road, rail, sea and air of the battalion and its families to Australia and the reception of the incoming 8 RAR and its families.2. I understand that Mr Walter Heagney, a former member of B Company, (B/4), has had his application for service and/or disability pension rejected because he was not allotted for service on the Malay Peninsula with 4RAR during the period. This rejection was supported by the fact that the Clarke Report concluded that 4RAR also was not allotted to the Malay Peninsula during the period September 1966 when Mr Heagney joined the unit as a reinforcement in Malacca and September 1967, when the battalion returned to Australia. The following excerpt is from the Clarke Report : 14.129 As part of the Australian forces committed to Confrontation, 4RAR was allotted for duty in Malaysia, arriving in Sarawak in April 1966. The unit conducted operations there until 11 August 1966 when the conflict ended with the signing of the Treaty of Bangkok The battalion was then redeployed to Malacca for peacetime duties, after which reinforcements joined the regiment. Those members of 4RAR who served in Borneo during Confrontation have full entitlements under the VEA because they were involved in warlike operations in connection with Confrontation. However, those who made submissions to the Review were reinforcements who did not join 4RAR in Malaysia until after its move to Malacca when Confrontation had ended. Even though the Malay Peninsula remained an operational area until 30 September 1967, no units were allotted to the area after 14 September 1966, the date of which coincides with the withdrawal of 4RAR from Borneo and its move to Malacca. 14.130 In considering whether the service of 4RAR in Malacca was warlike. the Committee notes that the official Army history states: At the conclusion of `Confrontation' in early September the bases occupied by 4RAR were handed over to 3 Royal Malay Regiment (3 RMR). By 10 Sep 66, 4RAR was completely relocated to Malacca ... 1967 provided peacetime soldiering at its best. "1751 14.131 In this regard, the Committee understands that the tasks of 4RAR in Malacca were garrison duties and jungle warfare training. 14.132 The fact that Malaysia remained an operational area until 30 September 1967 does not mean that all units that served in the operational area up until that time were regarded as having eligible service under the VEA, because the VEA also requires that a person be allotted for duty in the operational area. Allotment demonstrated that the person was engaged in activities connected with a warlike operation or state of disturbance. The Committee understands that the 30 September 1967 cut-off date under the VEA was the day before the date of commencement of Statutory Rule 1967, No. 134, which repealed the Special Area Regulation deeming the area as operational, and was the date 4RAR returned to Australia. It appears that 4RAR was not allotted to any operation on the Malay Peninsula after 12 August 1966 but remained a contingent force for redeployment on operations if hostilities resumed, which they did not. 14.133 The service by 8RAR, which replaced 4RAR, mainly involved exercises and `work up' for a tour in South Vietnam. 14.134 The Committee concludes that service in 4RAR and 8RAR on the Malay Peninsula after the end of Confrontation was peacetime service and does not meet either the warlike or the non-warlike service criterion.

Warlike and non-warlike service' are terms the Australian Defence Force (ADF) has used since 1994 to classify service for the purposes of pay and conditions. In 1997, definitions of warlike and non-warlike service were inserted into the VEA by the Veterans' Affairs Legislation (Budget and Compensation Measures) Act 1997 effective from 13 May 1997. 10.9 Warlike service' under the VEA is defined in s. 5C (1) as service in the ADF of a kind determined in writing by the Minister for Defence to be warlike service. A declaration of warlike service gives access to compensatory payments such as the disability pension. It is also qualifying service for service pension purposes under the VEA. In 1993, Cabinet agreed that warlike service refers to those military activities where the application of force-is authorised to pursue specific military objectives and there is an expectation of casualties. These operations encompass but are not limited to: a state of declared war, conventional combat operations against an armed adversary, and peace enforcement operations that are military operations in support of diplomatic efforts to restore peace between belligerents who may not be consenting to intervention and may be engaged in combat activities (normally, peace enforcement operations will be conducted under Chapter VI/ of the United Nations Charter, and in these cases the application of all necessary force is authorised to restore peace and security). 4. To emphasise Lt Col Avery's point above, the Mohr Report noted deficiencies in the manner in which past reviews failed to research adequately or to analyse researched material adequately and therefore reached questionable conclusions: Research and Analysis A great deal of Cabinet and other high level documentation was accessed from National and Defence Archives. On some occasions this material provided a perspective on the background to an alleged anomaly quite different to that stated in past reviews. It seemed to me that this material had not been previously researched or, if it had, it had not been carefully analysed, before past decisions were taken. 5. Justice Mohr warned that any such errors do not stop where they are made. They take on a life of their own and the error is compounded : Failure to conduct proper research and analysis of the background issues has led to some personnel being given incomplete or flawed information or advice. Each and every time the suspect information was regurgitated to a new claimant, it took on a more enhanced authenticity.Note: Al emphases throughout this document are mine. 6. A clear understanding of a movie, discussion or argument et al, is more difficult if not impossible, if the raison d'etre or other vital clues and issues are missed by a late entrance. This was Justice Mohr's view : One of the principles followed by the Review in examining whether or not an anomaly had occurred was, as far as was practicable, to research and understand the raison d'etre for ADF deployments to South-East Asia. This close scrutiny has found, in my view, that some aspects of procedure and process in administering entitlement to medals and repatriation benefits are themselves in need of clarification or review. 7. Without understanding the raison d'etre for ADF deployments to South-East Asia in that era, to use as a reference benchmark against which subsequent service anomalies of the time can be compared, any retrospective examination is doomed to conclusions based on personal preferences or opinions or other non-objective and partial agenda. 8. Justice Mohr makes this further point under Responsibilities of the Departments of Defence and Veterans' Affairs : "....when the nature of past defence force service is being reviewed, it is axiomatic that those who understand the nuances of what is involved should do this." Axiomatic is not a suggestion. 9. I shall be apologetic and pleased to stand corrected but with no disrespect at all intended, it does not appear that much attention was paid to that unambiguous recommendation in the selection of the very next committee to review past defence force service. I would have thought that any 4 RAR officer who served with the battalion during this period would be worth interviewing to get some understanding of the nuances of what was involved. I have no idea if any other 4 RAR officer was interviewed. I have no legal qualifications or training and save for Courts-Martial experience as a Defending Officer, no conventional legal experience but I did serve as an infantry officer with 4 RAR in Australia, on the Malay Peninsula and in Sarawak, including leading a 10-day, platoon-sized, illegal armed invasion of Indonesia, euphemistically termed a "cross-border" patrol. I subsequently served as the GSO3 Intelligence and then GSO2 Operations of the 6th Task Force and as the GSO3 Intelligence of the 1St Australian Task Force in Vietnam. Military history is my main interest and I have a working understanding of the nuances of what was involved in Australian Army deployments to South-East Asia in that era.10. The Australian Government does not now and did not over the last five decades, casually commit forces overseas. Between the end of the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces' (BCOF) commitment in Japan and prior to the complete withdrawal of Australian forces from Vietnam in the early 1970s, no large contingents of the Australian Army were deployed into SE Asia for peacetime or training purposes. So for Australian forces overseas in that period, it was not peacetime soldiering. Between Korea and Vietnam, the only significant overseas deployment of Australian troops was to 28th Commonwealth Infantry Brigade Group (28 CIB), a component of the British Far East Land Forces (FARELF), located in Terendak Garrison at Malacca, Malaya (subsequently Malaysia), with the overall command HQ Australian Army Force (HQ AAF FARELF), located in Singapore. These were part of the Far East Strategic Reserve (FESR).

12. As can be seen, the raison d'etre for the employment of Australian forces in the FESR was to counter Communist aggression in SE Asia and to defend Malaya and Singapore. This evolved into the "domino theory" which was the concept of `forward defence' - the `better to fight them before they reach Australia' philosophy and the prime reason given why troops were committed to Vietnam. Neither FESR role was a peacetime role in the same sense that service in Australia at that time was peacetime service, because in Australia, absolutely no threat from armed anti-government forces existed and in SE Asia, it did and still does.13. Consequently, armed troops who were sent to deter and counter such armed anti-government forces by operating against them, were automatically in harm's way. Under the ADF's 1994 definition of `warlike service' inserted in 1997 in Section 5C (1) of the VEA 1986, these were: "conventional combat operations against an armed adversary.... with an expectation of casualties" (see paragraph 3 above). No amount of revisionist rewriting of history or reworking of definitions of what was warlike and what was non-warlike and what was neither, four decades or more earlier, can change that. 14. Under the umbrella of the FESR's aggressive/defensive execution of the primary and secondary roles in the defence of Malaya/Malaysia and Singapore, the accepted threat varied in intensity from time to time and the status of the area vis-a-vis entitlements to repatriation etc benefits, changed according to Australian Government assessments and decisions. Following the signing of the 11 Aug 1966 Treaty of Bangkok, the Malay Peninsula continued to be an operational area in terms of the Special Overseas Service Act (SOS) 1962, until midnight on 30 Sept 1967.

a. In May 1965, The Minister for Defence advised the Minister for Repatriation that: "The whole of the Federation of Malaysia has now been proclaimed a security area under the [Malaysian] Internal Security Act. Indonesian infiltrations have occurred in various places on the Malayan Peninsula, including Malacca, Johore and Singapore. The Joint Intelligence Committee's view is that they will continue and will not be confined to any particular areas. _ Australian ground forces have been engaged against infiltrators in Malacca in addition to their operations on the Thai/Malay border and in Borneo. _ Plans for defence of the Malayan Peninsula against infiltrators divide Malaya into regions for which various brigades are responsible. 28 Commonwealth Brigade[encompassing ADF Army Personnel] is responsible for Malacca. However, this would not necessarily preclude their use elsewhere in an emergency and if suitable other forces were not available. _ Australian naval and air forces are also available for use against Indonesian infiltrators and our air force participates in the air defence alert in the air defence identification zone over Malaya/Singapore.

17. According to the Government's own sanctioned table, members on posted strength during the period August 1965 when the 4 RAR advance party arrived and 30 September 1967, qualified for the GSM 1962 with Clasp 'Malay Peninsula', plus qualifying service for both disability and service pensions. This subsequently included the Malaysian PJM. So what is the purpose forty years later of legislating to deny these men their earned entitlements?18. If that is an incorrect interpretation, then the table above and Cabinet Decision 1042 of 7 Jul 1965 are ambiguous and the Mohr committee's interpretation of the Cabinet Decision and Item 7 of Schedule 2 to the VEA 1986, was wrong. If they are not ambiguous and the interpretations are correct, the members were wrongly denied their entitlements and the situation should be rectified without delay. 19. Members on posted strength during that period in addition to those who arrived from Australia before the forward echelon was deployed to Sarawak, included :

20. As part of the FESR's secondary role, Australian forces tracked down, engaged and killed and wounded Communist terrorists (CTs) in jungle patrols on the Malay Peninsula and the Thai/Malay border region. Later, they intercepted and captured armed infiltrators from Indonesia on the lower Malay Peninsula. This is why the FESR was raised and then located in Malaya and then Malaysia and Singapore. This role could not be effectively carried out from Australia, Britain or New Zealand. Hence it cannot even be remotely equated to service at home. 21. In the primary role, Australians had major engagements with Indonesian regular Army units in the jungles of Sarawak, in which they killed and wounded Indonesian soldiers and were killed and wounded themselves or otherwise died or were injured. They also launched numerous top secret, highly-illegal, armed invasions deep into Kalimantan, Indonesia from their bases in Sarawak. The reason both 3 RAR and 4 RAR were deployed to Sarawak from Malacca, was because as stated above, the primary role had precedence over the secondary role and the British, New Zealand and Gurkha battalions remaining in Malacca were available to fill the secondary role. 22. It seems from the evidence in its report that the Clarke committee made an inexplicable albeit significant error in regard to 4 RAR's service on the Malay Peninsula. The Clarke Report notes : As Dad of the Australian forces committed to Confrontation, 4RAR was allotted for duty In February 1965, 3RAR and a Special Air Service (SAS) squadron were sent to Borneo at the request of the Malaysian Government. 3RAR was replaced in April 1966 by the 4th Battalion Royal Australian Regiment (4RAR)

24. The Clarke committee understood that 4 RAR moved from Sarawak to Malacca and was not allotted to any operation on the Malay Peninsula : It appears that 4 PAR was not allotted to any operation on the Malay Peninsula after 12 August 1966 but remained a contingent force for redeployment on operations if hostilities resumed, which they did not. Even though the Malay Peninsula remained an operational area until 30 September 1967, no units were allotted to the area after 14 September 1966, the date of which coincides with the withdrawal of 4RAR from Borneo and its move to Malacca. As Justice Mohr pointed out, this understanding is to not understand the raison d'etre for deployment to Malaysia. 25. 4 RAR did not need to be allotted to any operation on the Malay Peninsula after 12 August 1966. It was already allotted to the Malay Peninsula, which was already an operational area as was Sarawak. After its service in Sarawak, 4 RAR's forward echelon simply returned to its lines in Malacca to rejoin its rear echelon and the battalion resumed its duties in the Far East Strategic Reserve.

26. 4 RAR did not withdraw from Borneo and move to Malacca on 14 September 1966. I believe the unit records will show that the battalion was complete in Terendak Garrison, save for a small rear details' party, by 5 September 1966. 27. The Clarke committee also notes that hostilities did not resume. That observation enjoyed the infallibility of hindsight. 4 RAR and the Australian Government from which the battalion received its orders, had to act on current Defence Committee assessments of the time. Those assessments noted that : "... having regard to the inability to predict in what areas infiltrators would operate, the continued activity in this a) It is simply unrealistic and naive for the Clarke committee to make such a judgment in hindsight almost 30 years after the events. The Defence Committee's assessment and the Australian Government's declaration of the Malay Peninsula as an operational area remained unchanged until 1 October 1967. Those were the factors which determined whether 4 RAR's service on the Malay Peninsula before or after its return from Sarawak until 30 September 1967, was warlike or non-warlike.

29. The status quo on the Malay Peninsula remained unchanged during 4 RAR's 4-month deployment from the Malay Peninsula to deal with heavier and more continuous Indonesian incursions into Malaysian territory in Sarawak. Sarawak is not a separate country from Malaysia. It is a state of the Federation of Malaysia, separated by sea from the mainland Malay Peninsula, just as Tasmania is a state of Australia separated by sea from the mainland. The Australian Government had access to current intelligence and threat assessments at all times. It could not be pressured by external parties to make decisions or take action against its will. If it had seen fit to change the status of the area, it was free to do so. It did not do so until 1 October 1967. 30. Some errors of fact in the Clarke Report are testament to the fact that the people who accepted the report and others who acted on it, had absolutely no idea of that period in Australian military history. For example from the Clarke Report : a) Confrontation ceased

with President Sukamo's fall in 1965, and a peace treaty 31. This is the only reference I have ever come across, which mentions a peace treaty ratified in Jakarta on 11 August 1965, between Malaysia and Indonesia heralding the end of Confrontation. If Confrontation ceased on 11 August 1965, why was 4 RAR deployed to Sarawak in April 1966 with full repatriation benefits? And if 1965 is just a "typo" for 1966, is Jakarta also a typo for Bangkok? On 1 October 1965, five Indonesian Generals were murdered in their homes as part of a coup and General Suharto replaced General Sukarno as President. No peace treaty with Malaysia was involved.32. In April 1966, the battalion was deployed from its base on the Malay Peninsula to Sarawak. It left behind a rear echelon to service the forward echelon in Sarawak, maintain the unit's lines in Terendak Garrison, protect and otherwise look after the battalion's families and receive and employ reinforcements from Australia, until the return of the forward echelon from Sarawak. This rear echelon was critical to the battalion's optimum operational performance in Sarawak. Hence 4 RAR served on the Malay Peninsula before during and after its deployment to Sarawak. 33. In relation to service on the Malay Peninsula after the battalion's service in Sarawak, the Clarke committee concluded that it was peacetime service. It based its conclusion on what it termed 'official Army history' but as best I can find, did not specify the reference. However the quote used below by the Clarke Report is contained in an official Army history titled "Malayan Emergency 1965-1968" at the following web address : Note: For the record, just as there was no. peace treaty signed in Jakarta in August 1965, there was no Malayan Emergency between 1965 and 1968. This is typical of the sloppy, inadequate, unacceptable, indifferent and careless research referred to by Justice Mohr. Qualifying service is at stake and a Government review committee bases its conclusions and recommendations on an "official Army history° which headlines an event which never happened and nobody involved in the entire Government knew the difference or bothered to check. It is as a result of this kind of ignorance that Justice Mohr noted in paragraph 8 above, the mistake takes on an enhanced authenticity. b) In considering whether the service of 4 RAR in Malacca was warlike, the Committee notes that the official Army history states: "At the conclusion of 'Confrontation' in early September the bases occupied by 4 RAR were handed over to 3 Royal Malay Regiment (3 RMR). By 10 Sep 66, 4 RAR was completely relocated to Malacca ... 1967 provided peacetime soldiering at its best."In this regard, the Committee understands that the tasks of 4 RAR in Malacca were garrison duties and jungle warfare training. 34. This single statement by an unidentified author, unsupported by any other reference and backed only by a claim that the battalion which was already allotted to FESR duties on the Malay Peninsula was not allotted to any specific operation there, is tendered as proof that 4 RAR's service in Malacca after Sarawak was not warlike. I was present as a witness at numerous hearings at sub-unit and unit level in both Australia and Malaysia. No charge sheet in Australia, viz the Australian Army Form A4 (AAF A4), ever contained the words While on War Service or the abbreviation WOWS. In Malacca during 4 RAR's deployment there as a unit in the FESR, all charge sheets contained in the wording of the charge against a soldier for misconduct, the words WHILE ON WAR SERVICE or the abbreviation WOWS. If service on the Malay Peninsula was the exact equivalent to service in Australia, why was this difference in the wording of the charge sheets?35. The Clarke committee determined from an 'official Army history', that 4 RAR's service on the Malay Peninsula after Sarawak in 1966 was "peacetime soldiering at its best" and did not meet the (1994) warlike or non-warlike criteria of the VEA 1986. It would require significant spin, to define "war service" as "peacetime soldiering at its best" and at the very least, the Clarke committee should explain how it did so. I presume a unit cannot be simultaneously on war service and peacetime service and as I recall, the penalty levels increased with War Service and Active Service. So it should have very important legal and other ramifications if all soldiers who were charged and punished under war service conditions in Malaysia in 1966-67, were found four decades later, to have been incorrectly charged and punished. Ignoring any possible claims for compensation, the court case alone would be expensive for the taxpayer. 36. The Clarke Report notes that 4 RAR conducted operations in Sarawak until 11 August 1966 when the conflict ended with the signing of the Treaty of Bangkok. This clearly implies to the uninformed reader that 4 RAR's operations in Borneo ceased on 11 August 1966 when Confrontation `ended' and the unit was redeployed (an incorrect use of the term) to Malacca, presumably as soon as practicable thereafter. The official Army history used by the Clarke committee also notes that Confrontation 'concluded' in early September 1966 (not 11 August 1966) while the Committee itself says that Confrontation 'ceased' with the fall of Sukarno in 1965. Multiple choice. 37. The facts on the ground in Sarawak, were these: 38. The Clarke committee relied on "official Army history" for its 'understanding' of critical facts. Unfortunately, official histories, Army or otherwise, are unreliable at best for many reasons. Justice Mohr notes one flagrant example : a. It is axiomatic that one must get the facts right in an area as sensitive as Honours and Awards. This, however, was not a/ways the case. A prominent example is the official distribution of a flawed table of ships allotted to the Far-East during the Indonesian Confrontation. This flawed list has, until now, denied some personnel being awarded campaign medals and repatriation benefits. It behoves the Services to get it right the first time, an error such as this is indefensible. I 41. One example of historical material not available for examination is Cabinet secrets. These are released every New Year's Day, thirty years after the fact, to ensure that memories have dulled, major players will have passed on and it will be of nothing more than prurient interest to the general public. Any `official Australian Army history' written before 1996, would not have included Australia's (and others') armed invasions of Indonesia during Confrontation, because the British Cabinet did not release the documents containing the admission until then and then it did so very quietly. So any retrospective examination of Borneo as to why certain events happened or didn't happen, would need to include those facts but it couldn't, because the facts were not available and were therefore unknown to the historian. Hence the 'official history' could not be considered totally reliable. No official history can be. Refer to the official Japanese histories of World War 2. History is one person's opinion, based on a theory that he or she holds about what happened and supported by known facts selected by the author to `prove' that theory. a) For example, a very senior Indonesian commander in Kalimantan did not know until many years later, that his life was 'spared' by a 22 SAS patrol which had set a river ambush for him deep in Kalimantan. Just as his boat entered the killing ground, some nubile young women appeared on the deck. Although there was no question the target was aboard the vessel, the patrol commander decided not to take innocent civilian lives and never triggered the ambush. A few years ago, the General involved was a guest of 22 SAS Regiment in Hereford UK and he presented the former members of the patrol with gifts for sparing his life. The repercussions of his death would have had a significant impact on Indonesian operations in Borneo - and vice versa but the uninformed could not possibly know why until 30 years later and then only if they found out.42. So for determining repatriation benefits for warlike service in Sarawak, what should be the cut-off date? What if any is the significance of 11 August 1966 in terms of repatriation benefits and qualifying service and why is it continually mentioned in service reviews? Should a reinforcement to 4 RAR in Sarawak on 12 August 1966, not qualify for the GSM 1962 with Clasp "Borneo" and qualifying service for all repatriation benefits, because according to one inaccurate 'official Army history', the conflict ended the day before? Would everyone on posted strength in Sarawak until midnight 1 September 1966 qualify, or would it be the date the battalion was complete in Malacca, marking the actual end of its deployment to Sarawak? And when was the date the battalion was complete in Malacca - when the main body arrived back or when the rear party arrived back? 43. How would a former soldier with no access to Cabinet records and other high level documentation from National and Defence archives, ever be in a position to convince DVA, the VRB and/or the AAT, that he was on an operational patrol in Borneo on 21 August 1966, when the Government says 4 RAR stopped operations on 11 August 1966? The soldier knows he is right and he is and the Government thinks it is right - but it isn't. So his application is rejected as are others and the incorrect Government position, as Justice Mohr points out, takes on an enhanced authenticity by regurgitating material which had either not been researched at all or not carefully checked and analysed. 44. Justice Mohr observed : The Repatriation Legislation in force

covering the period of Confrontation was the Repatriation

(Special Overseas Service) (SOS) Act 1962. Under this Act,

eligible service depended on being `allotted' for `special

service' in a 'special area' and actually serving in

a

`special area'. Service in

a `special area' while allotted for special duty meant service

that was directly related to the warlike operations or state of

disturbance in the area. 48. From the Mohr Report : As discussed in detail under that part of this Report dealing with the anomaly of seagoing Naval forces of FESR, because of the administrative difficulties in administering this 'on duty' concept, Cabinet decided that eligibility for repatriation benefits would be afforded on the basis of `any occurrence' while allotted to FESR ie, actual engagement with the enemy was not a prerequisite for eligibility, only being allotted for duty with FESR was sufficient. This was a Cabinet decision. How can it possibly be ignored? 4 RAR was an FESR unit operating in a declared operational area. What administrative oversights or shortcomings may have been involved in retrospect are irrelevant. The unit did not get there without being ordered there by the Government. 49. Justice Mohr concludes : Given the treatment of those allotted to FESR, it would be anomalous to require Army and RAAF personnel on the posted strength of units located on the Malaya Peninsula, including Singapore, during the period of Confrontation from 17 Aug 64 to 30 Sep 67 inclusive, to have been actually under direct fire from Indonesians before being eligible for repatriation benefits.a) Conclusion It is my opinion based on the facts presented that there is an anomaly in the repatriation and medals entitlement afforded to Army and RAAF personnel on the posted strength of units located on the Malayan Peninsula, including Singapore, during the period of Confrontation from 17 Aug 64 to 30 Sep 67. Their service "was directly related to the warlike operations or state of disturbance in the area". Their service was similar in character and level of danger experienced by their Navy colleagues. There does not seem to be any supportable reason, therefore, to deny Army and RAAF personnel similar repatriation benefits and medals entitlement to those received by their Navy colleagues who were allotted for duty during the period of Confrontation. Roger J. Wickham 4 RAR - 1964-1967 Inclusive |